There is a poison flowing through our lives at the moment, it is showing up in our families, across our society, and literally threatening the entire planet. We can all point to the symptoms, they are legion and are leading us closer and closer to a precipice none of us ought to be anywhere near. A common feature of the toxin is its ability to cause its victims to isolate behind the high walls of their tribe, to turn their back on their neighbors, to shun members of their own family, and in the end, to give up hope. All of us are guilty of this to one degree or another, the rationales and the details are interchangeable, which makes those pesky facts and realities beside the point. In every case though, the poison is the same, we seem to have chosen to respond to the existential upheaval in our lives by giving up.

photo by Zac Durant on Unsplash

Judith Thurman, in a piece in the New Yorker a few months ago wrote, “ … in an era of cataclysmic strife, weather, and unreason, hope is as precious as it is scarce.” To even speak of hope these days seems almost quaint, a remnant from a time before polarization came to be, inexplicably, sensible. But when was the last time you heard someone say they felt ‘hopeful?’

It need not be this way. Socially, politically, religiously, ethically, morally, by any measure, we are burning through what little remaining equity of decency we might still lay claim to.

photo courtesy of endtimes.news

But the moment is actually offering an opportunity to see ourselves in a different light –– so that instead of trashing each other, we might try listening to one another; so that instead of tearing down norms just to teach somebody a lesson, we might collaborate on solutions; and instead of breaking everything (as cute as that phrase might once have been), can we imagine an entirely new approach where possibility supersedes what seems inevitable?

Listening, collaborating, entertaining fresh possibilities, these all speak of an approach that allows for the unexpected, in fact it looks forward to being surprised by what may yet be. This might describe a person as being hopeful, but it holds none of the sense of hope for a designated outcome. In fact it is just the opposite. What it does define is a person who embodies what hope points to, living not in hope for anything, but living in relationship with reality’s promise, found precisely in its uncertainties.

And despite what you have read, hope is not dead.

“Hope deferred makes the heart sick.” Proverbs13:12

Am I, are you, ready to be hope? That quaint notion that a single voice has something valuable to offer? Hoping for something is not about ‘my’ cause, but about ‘our’ cause, ‘our’ shared thriving. Hope is not a thing to find and latch on to, it is not even a proper noun, nor is it a naive optimism banking on some idealized future when everything is going to turn out just like I planned.

Rather, to live with hope, to be hopeful, reveals a belief about yourself that is best described as a position taken with respect to reality. It is your personal answer to forces, which at the moment are arrayed against your human thriving. Some forces in fact endangering your survival. In such a context, being hopeful, being hope, shifts your default setting towards a generosity of spirit. This ‘stance’ is a response to reality you and I individually choose to adopt –– it accepts, it adapts and then responds. Coming from a sense of inner resourcefulness, accepting that our uniqueness and individuality can only be meaningful when the focus is taken off ourselves and put on others, we respond to the reality of the moment by caring for all we encounter.

To care is our sacred obligation to life, our own and the life of all who will follow, that calls for something heroic, something creative, something that binds us to each other rather than causing any more separation.

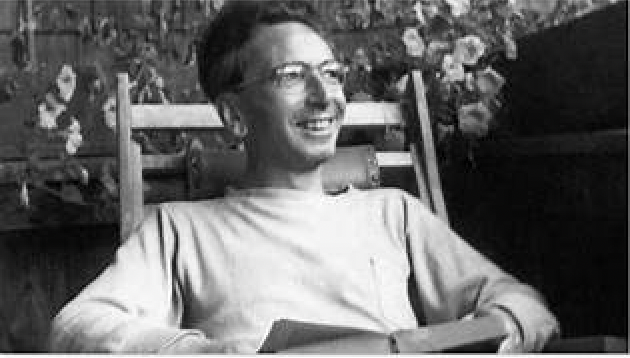

photo courtesy of sott.net

Hope is not about the future. Viktor E. Frankl, Austrian neurologist, psychologist, philosopher, and author, in his 1946 book, Yes To Life, wrote of his experiences as a prisoner in Nazi concentration camps. He writes that the unspeakable conditions and treatment in the camps caused him to question if meaning had ceased even to exist. Frankl concludes that for humans, “ … life itself means being questioned,” … and that, “meaning exists in the act of answering … no longer in words but only in deeds, and more than that in living, in our whole being.” So we are left to choose what our personal response is to be as hopelessness tries to have the last word.

Being the thing hope points to requires no inside information, it does not demand superhuman courage, and does not presume there is only one answer to any problem. To actually be hope, is to buy into the concept, to ‘be not afraid.’ Which is not an absence of fear, do not trust anyone who claims this, but is trusting in the generosity of the spirit which exists within you. It is enough to go on, even in the face of so much.

This is meaning Frankl wrote “exists in the act of answering.” And in our ‘answering’ each one of us becomes hope, heroically sticking with what is, the reality we have and the choice we have made. Living then as hope ‘in our whole being’ provides your antidote to the poison seeping throughout our world.